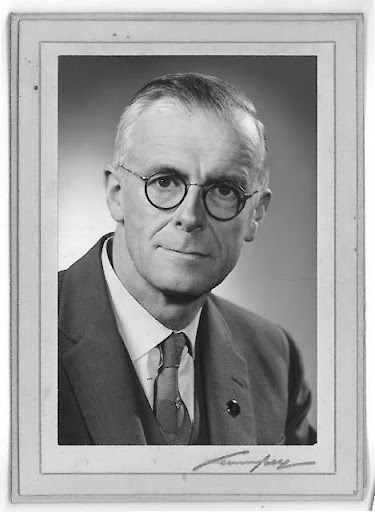

Some thoughts and Musings on a Gentleman and a scholar- Ross Beckingham (son-in-law)

To say I was fond of Warrington Taylor (or “Granddad” as he was affectionately called by all in our home) would be an understatement…over the years we were privileged to have him living with us in our home at St Clair - Dunedin, I first deeply respected, and then in time - grew to love him dearly.

Karitane, Otago, a place where Warrington Taylor spent many holidays with his family. Photo: Brian Taylor

I loved his eccentricities. I loved his pragmatic and intelligent dialogue on almost any subject you could imagine. He never “paraded” his vast knowledge, or made you feel inferior if (as was the case many times) the conversation became a little complex for me, he would instead just draw a big breath and explain himself in simpler terms. He was an inordinately patient man!

Grandad was probably the most honest and sincere person of his generation I have ever met. His reputation in the legal fraternity and with those of his older clients continued long after he retired from the legal practice. On many occasions he would say: “I’m off to visit “Miss So and So” in Maori Hill-she’s an old client and wants me to check out some papers for her and as long as I am visiting Catherine - it’s not out of my way”. His wife was at the time hospitalised in Marinoto Clinic, and he religiously visited her every day. I don’t believe he missed more than half a dozen days the whole time she was alive and cared for at the hospital-a tribute to his love, devotion, and so typical of his attention to doing the “right thing” by people. If he couldn’t visit her - he rang and spoke to her.

All of this advice to old clients would of course be completely free of charge-it would never occur to him to either ask, or accept, any remuneration for his time. He believed client relationships were for life. We of course teased him mercilessly about his “afternoon assignations with the old ladies” – all of which he endured with a wonderful spirit, and an embarrassed smile.

On the few times I visited with Suzanne at the Highgate family home, I was always treated with courtesy and warm hospitality. On one memorable occasion he quietly took me aside and asked “Had I ever been up top?” Seeing my bewilderment he whispered “Come with me…it will be our secret?” He proceeded to show me the way up a ladder into the roof cavity of the family’s giant home –literally a football pitch in size! But this was only the beginning –we then climbed through - and out onto the slate roof itself. Grandad had marked out on the roof an elaborate system of numbered markers beside the individual slates that were his “stepping” stones for a safe excursion out on the roof-just another example of the mans delightful practicality. He guided me up - one foot after another, using marker one-(right foot), marker 2 (left foot) and so on. Once on the top of the roof gable he sat me down beside him our feet straddling the horrifically high gable, and the view from this vantage point was breathtaking! A full 360 degree vista across to the Mosgiel plains in the West right around to Mt Cargill in the North, and then further around to the harbour heads and all the way up to city itself with harbour and the southern and eastern suburbs sparkling in the sunshine, and then finally to the South. This view and memory will last with me forever! Retracing our steps, we climbed inside and before closing the trapdoor Grandad whispered again-“Remember…it’s our secret,- we won’t mention this to Catherine-she wouldn’t approve!”

Some of the most fun times we had together were washing and drying tea time dishes at night. Suzanne having cooed tea for the family, would leave to organise children’s homework and stuff for the next day, and Warrington and I would take probably 3 times longer than necessary to wash and dry the dishes discussing all kinds of things and setting the world to rights. We were often chastised by Suzanne for taking far too long-but it was the banter-not the task we enjoyed, and I know he enjoyed it equally as much as I did.

I wasn’t really able to do much for him by way of “pampering”, but we did develop a rather lovely scenario where last thing at night I would make him a Milo or Hot Chocolate drink, (he was a prodigious chocolate eater) throw a white tea towel over one arm and carry a hot drink and plate with (always) a couple of chocolate biscuits down to his bedsit to present to him for supper. The scene never altered…a tap on the door. “You rang M’Laud” I would say, introducing myself, and when he called me in, he always said the same thing: “Oh Ross, …..RICH!” You are really too kind”. We both enjoyed this little interlude immensely.

Stand out memories would be:

His remarkable recovery from Parkinson’s disease:

When he first came to live with us he was physically very frail and worn out from a long stint of caring for Catherine at Highgate. I would have to cut his meat on his plate into bite size pieces as he hadn’t the strength to do so himself. After a few weeks on a course “Sinimet” (the wonder drug of the day-apparently) prescribed by family doctor Jim Reid, he was up and doing for himself - all manner of things, including walking up to catch the St Clair bus into town, and then visit Catherine-a remarkable turn around in health, and we were lucky he enjoyed good health for the four or so years he spent with Suzanne and I and the children.

His obsession with “altering” things which were on the face of it - perfectly serviceable:

On one occasion I went to see him in his room, to find he had drilled a hole in the Queen Anne Mahogany headboard of his bed to install a (highly illegal) “ganged-up” three pin plug arrangement into which he was able to plug his kettle, his TV, and his electric blanket! On retiring at night last thing he would reach up and switch them all off. “See - it’s much more convenient Ross.” You could not fault the reasoning- only the necessity?

His work on the Taylor and McCarter Family Trees:

He was able to share a lot of this history with our children all of whom were very interested-especially our daughter Tanya-with whom he spent a great deal of time explaining and copying out family history for.

His love of reading:

He was the most voracious reader I have ever met. He also had the rather annoying habit (from my sense of tidiness anyway) of underlining points or paragraphs of interest to him throughout a book in red pen! Never pencil - that might be able to be removed…always red pen!His habit of cutting his toast in the mornings:

Always done to match the size of the mosaic tiles set into the top of the breakfast bar in the kitchen-“Perfect bite-size pieces-Ross!”

His habit of eating peas-one at a time!

Often a little frustrating while we waiting to clean up at night, and the children often looked in anguish at the number of peas still to be devoured so they might be able to leave the table!

His excitement and great joy of meeting up with his brother - after 52 years apart!

In conclusion, he once said to me: “The measure of a persons worth in this life Ross, is usually directly related to the amount of times they are thought of or spoken about - once they are gone.”

If this is the case then “Grandad” will never be forgotten, and his worth is priceless!

Saturday 28 August 2010

Sunday 22 August 2010

A few thoughts on Dad by Brian Taylore, his son.

These are isolated and in no particular order.

22.8.10

Dad was a very compassionate man, always willing to help people especially those who were not well off. I discovered quite early on in life that he has been acting for people as quite a young lawyer without charging them at all or at best very little. Being a strong socialist he always wanted to help people who were not well off. He believed in equality for all people.

The first I can remember about dad was being woken up in the morning. When we were living out on the Taieri Plains (Janefield) almost on the dot of 7.00 when the horn when at the Mosgiel Wollen Mills to get everyone to come to work, dad would come into our bedrooms and literally “whistle us up!” This consisted of about 5 or 6 whistles use for calling dogs over. Not that we were ever thought of as dogs, it was his way of making our wake up fun. The trouble was it carried on into my late teens and early university days when we moved to 204 Highgate Dunedin. This was increasing more annoying after I had had a long night out on the town. Sometimes he would receive a pretty sharp response from me, however dad carried on with the practice always in good humour. I think it was more of an ongoing joke as I got older. It would also happen even when I had a friend to stay over.

Being a pragmatist, dad thought about having me baptised, but he knew he could not go along with the idea that I should be brought up in the religious belief of the Presbyterian church. He went to see the minister and asked if he would be able to modify the service so that all reference to God was eliminated, (however he always accepted the sentiments of a young person being raised as a caring compassionate person). In 1949 this was an impossible idea, so dad dropped the whole plan.

I can remember when my dear sister came on the scene. Dad loved her dearly, he was very pleased that Suzanne and I got on so well together – and still do. This was a very important part of his family thinking, people getting on well with each other and giving total support. I remember being taught this from a very early age.

I had my jobs to do at home from when I was quite young. This included keeping the hedge in front of the property trim and later the large macracarpa hedge along the south side of the property. We use to build “nesting” places in the hedge. On a few occasions we would hide in there, so that dad had to find us to come in for our evening meal. We would remain silent and dad would go along with the game, but he always knew where we were. We couldn’t fool him!

I do remember being on a strict vegetarian diet until I was 5 years old. This was my mother’s idea to overcome the asthma that I had from birth. I don’t think that dad really believed that this would work, but being dad he always kept an open mind and supported mum’s idea. Incidentally it seems as if it might have had a positive affect, I have not had asthma since.

Same thing when I was a competitive swimmer and in order to increase my size and strength mum organized for me to go to Tom Bolton’s private gym. This was always around 5.0 pm so poor old dad had to do a lot of extra running around after work to pick me up to get home. He always did it with good grace and total support.

I was a person who struggled at school. After the results of school certificate came out and it showed that I had failed. Instead of chastising me for not working hard enough (as that was the case), he simply said “If you would like to continue back at school, we will support you!” That was the greatest incentive and it stimulated me to work harder than ever. I finally got there and it was always with wonderful support from mum and dad. Nobody could ask for more.

I recall when in my first year at university I came home a bit drunk. I was creeping up the stairs when my mother called out. I though I would act as normal as possible so walked into my parant’s bedroom, turned on the light, shook them each by the hand and said good night. I turned and walked straight into the open door, almost knocking myself out. Dad got up help me into bed without a word and nothing was mentioned about the incident in the morning. I think he thought I had had punishment enough! All he had was a wry smile.

When I was training the runners I was coaching, we would spend two weeks out at Karitane (just north of Dunedin), over the Christmas – New year period. We got permission to mark out a training running track at Cherry Farm, this involved dad in calculating the length of the straits and the circumference of the curves for us so that we could scratch it out on the grass. Of course, when we were training, we needed a time keeping and who was that? Dad, of course. He never missed a day. This included taking us to the track meets on Boxing day January 2. He was always there for us, taking an interest in a sport he had never done, caring deeply about how the whole group ran - not just me. Those were great days.

Dad was a great anticipator. I remember a particular time at the funeral of my mother. We were waiting for the service to begin and I became very upset at seeing my mother’s coffin. Without looking at me dad, standing beside me, plunged his hand in his jacket pocket and pulled out a clean handkerchief, as if he knew that was exactly what would happen to me at the last minute before the service began.

22.8.10

Dad was a very compassionate man, always willing to help people especially those who were not well off. I discovered quite early on in life that he has been acting for people as quite a young lawyer without charging them at all or at best very little. Being a strong socialist he always wanted to help people who were not well off. He believed in equality for all people.

The first I can remember about dad was being woken up in the morning. When we were living out on the Taieri Plains (Janefield) almost on the dot of 7.00 when the horn when at the Mosgiel Wollen Mills to get everyone to come to work, dad would come into our bedrooms and literally “whistle us up!” This consisted of about 5 or 6 whistles use for calling dogs over. Not that we were ever thought of as dogs, it was his way of making our wake up fun. The trouble was it carried on into my late teens and early university days when we moved to 204 Highgate Dunedin. This was increasing more annoying after I had had a long night out on the town. Sometimes he would receive a pretty sharp response from me, however dad carried on with the practice always in good humour. I think it was more of an ongoing joke as I got older. It would also happen even when I had a friend to stay over.

Being a pragmatist, dad thought about having me baptised, but he knew he could not go along with the idea that I should be brought up in the religious belief of the Presbyterian church. He went to see the minister and asked if he would be able to modify the service so that all reference to God was eliminated, (however he always accepted the sentiments of a young person being raised as a caring compassionate person). In 1949 this was an impossible idea, so dad dropped the whole plan.

I can remember when my dear sister came on the scene. Dad loved her dearly, he was very pleased that Suzanne and I got on so well together – and still do. This was a very important part of his family thinking, people getting on well with each other and giving total support. I remember being taught this from a very early age.

I had my jobs to do at home from when I was quite young. This included keeping the hedge in front of the property trim and later the large macracarpa hedge along the south side of the property. We use to build “nesting” places in the hedge. On a few occasions we would hide in there, so that dad had to find us to come in for our evening meal. We would remain silent and dad would go along with the game, but he always knew where we were. We couldn’t fool him!

I do remember being on a strict vegetarian diet until I was 5 years old. This was my mother’s idea to overcome the asthma that I had from birth. I don’t think that dad really believed that this would work, but being dad he always kept an open mind and supported mum’s idea. Incidentally it seems as if it might have had a positive affect, I have not had asthma since.

Same thing when I was a competitive swimmer and in order to increase my size and strength mum organized for me to go to Tom Bolton’s private gym. This was always around 5.0 pm so poor old dad had to do a lot of extra running around after work to pick me up to get home. He always did it with good grace and total support.

I was a person who struggled at school. After the results of school certificate came out and it showed that I had failed. Instead of chastising me for not working hard enough (as that was the case), he simply said “If you would like to continue back at school, we will support you!” That was the greatest incentive and it stimulated me to work harder than ever. I finally got there and it was always with wonderful support from mum and dad. Nobody could ask for more.

I recall when in my first year at university I came home a bit drunk. I was creeping up the stairs when my mother called out. I though I would act as normal as possible so walked into my parant’s bedroom, turned on the light, shook them each by the hand and said good night. I turned and walked straight into the open door, almost knocking myself out. Dad got up help me into bed without a word and nothing was mentioned about the incident in the morning. I think he thought I had had punishment enough! All he had was a wry smile.

When I was training the runners I was coaching, we would spend two weeks out at Karitane (just north of Dunedin), over the Christmas – New year period. We got permission to mark out a training running track at Cherry Farm, this involved dad in calculating the length of the straits and the circumference of the curves for us so that we could scratch it out on the grass. Of course, when we were training, we needed a time keeping and who was that? Dad, of course. He never missed a day. This included taking us to the track meets on Boxing day January 2. He was always there for us, taking an interest in a sport he had never done, caring deeply about how the whole group ran - not just me. Those were great days.

Dad was a great anticipator. I remember a particular time at the funeral of my mother. We were waiting for the service to begin and I became very upset at seeing my mother’s coffin. Without looking at me dad, standing beside me, plunged his hand in his jacket pocket and pulled out a clean handkerchief, as if he knew that was exactly what would happen to me at the last minute before the service began.

Thursday 19 August 2010

The Otago Daily Times cost One Penny.

Warrington McCarter Taylor born 4th July 1905.

Birth notice

Taylor to James and Louisa Taylor on July the 4th, a son

Warrington Mc Carter at 368 George Street. Both well.

This is the story about my Dad. Suzanne Taylor

My earliest memories of my Dad were sitting on his knee while he read stories before bed.

In the morning he was always up early having breakfast and then riding on his bike to the Train Station at Wingatui and catching the train into town to work.

We lived in a 3 acre life style block on the corner of Wingatui and Factory road.

My Dad was always busy we had 3 cows ,lots of hens who roamed where ever they wanted to and a cat called “Toby” to whom we all loved.

We had a hugh vege garden to which both Mum and Dad were always busy in. I have vivid memories of my Father’s large strong body and hands wielding a huge pitch fork bringing compost into the garden and turning it over so effortlessly. We had everything in that garden that you could ever think of.

He built Brian a tree hut high in a hugh tree which over looked one of the paddocks.

Brian also had a play shed with a steering wheel in it.

If he wasn’t busy in the garden, milking cows or at work he would always be mucking around with machinery.

I remember going with Dad almost every Saturday morning to the Garage in Mosgiel while he worked on a motor, or some part of a car. He would ask the mechanic about something he wasn’t sure of and then go and work on it himself.

Sometimes he would take me into the pub on the other corner to get a well earned beer and then we would go home.

Also on a Saturday afternoon he would visit the local Presbyterian Minister in his Manse and they would discuss in length matters pertaining to the Bible and Christianity.

I remember Brian and I going to Sunday School but Mum and Dad were never there.

When I was 4 years old I remember Dad hiring the services of a Draught horse and rider to help with harvesting the hay. It was a long hot day and all the men worked really hard to cut and bale the hay but my most vivid memory was Dad’s huge strong body with the pitch fork all day tirelessly working to get the job done. Mum I think actually making scones for the men working. There may have been a beer at the end of the day too if I remember.

Previous to the Hay making day Brian and I would run and hide in the hay growing and make hiding places even although we were told not to flatten the growing hay.

Often too Dad had to go looking for Duncan our Uncle who would sometimes go for a walk and not come back. We usually found him some where near 3 mile hill but one time he got as far as Wakari which was a long walk.

Renovations were also a big thing in our family life and Dad pulled the whole front of the house out and modernised it to the 50’s look. I have photos of this.

At night I could hear him in the Lounge playing our Player Piano and I would drift off to sleep listening to some piece of Classical music.

In one of our cars that we owned I found a pipe one day and I asked him what it was for. He told me that he was trying to learn how to smoke but couldn’t quite get the hang of it cause it made him cough. Good job he didn’t eh.

In the School holiday’s Brian and I would catch the train into town and go and visit Dad at work. He would buy us a pie for lunch which was a real treat and we would sit in Miss Tate’s room and have lunch. That is where I met George Bell a great friend of my Father’s and they would play the Cello together and that was quite exciting too. Dad also had and played a Recorder he had a big one at work and a smaller one at home. Mum said he wasn’t very good at it but at work there was no criticism.

I only saw my Father cry once when I was a child and that was after a phone call telling him that his Father had died. We all stood together in a circle and had a big hug while Dad cried.

Dad often went away on Business trips to Wellington and he would visit his Father who lived there with his Third wife.

Every time Dad came home he would bring us a present and I came to wait impatiently for him to open his suitcase up to see what his gift was going to be .He bought me lots of dolls because he knew I loved them and I think even when I was 12 all I wanted for my Birthday was a doll.

Birth notice

Taylor to James and Louisa Taylor on July the 4th, a son

Warrington Mc Carter at 368 George Street. Both well.

This is the story about my Dad. Suzanne Taylor

My earliest memories of my Dad were sitting on his knee while he read stories before bed.

In the morning he was always up early having breakfast and then riding on his bike to the Train Station at Wingatui and catching the train into town to work.

We lived in a 3 acre life style block on the corner of Wingatui and Factory road.

My Dad was always busy we had 3 cows ,lots of hens who roamed where ever they wanted to and a cat called “Toby” to whom we all loved.

We had a hugh vege garden to which both Mum and Dad were always busy in. I have vivid memories of my Father’s large strong body and hands wielding a huge pitch fork bringing compost into the garden and turning it over so effortlessly. We had everything in that garden that you could ever think of.

He built Brian a tree hut high in a hugh tree which over looked one of the paddocks.

Brian also had a play shed with a steering wheel in it.

If he wasn’t busy in the garden, milking cows or at work he would always be mucking around with machinery.

I remember going with Dad almost every Saturday morning to the Garage in Mosgiel while he worked on a motor, or some part of a car. He would ask the mechanic about something he wasn’t sure of and then go and work on it himself.

Sometimes he would take me into the pub on the other corner to get a well earned beer and then we would go home.

Also on a Saturday afternoon he would visit the local Presbyterian Minister in his Manse and they would discuss in length matters pertaining to the Bible and Christianity.

I remember Brian and I going to Sunday School but Mum and Dad were never there.

When I was 4 years old I remember Dad hiring the services of a Draught horse and rider to help with harvesting the hay. It was a long hot day and all the men worked really hard to cut and bale the hay but my most vivid memory was Dad’s huge strong body with the pitch fork all day tirelessly working to get the job done. Mum I think actually making scones for the men working. There may have been a beer at the end of the day too if I remember.

Previous to the Hay making day Brian and I would run and hide in the hay growing and make hiding places even although we were told not to flatten the growing hay.

Often too Dad had to go looking for Duncan our Uncle who would sometimes go for a walk and not come back. We usually found him some where near 3 mile hill but one time he got as far as Wakari which was a long walk.

Renovations were also a big thing in our family life and Dad pulled the whole front of the house out and modernised it to the 50’s look. I have photos of this.

At night I could hear him in the Lounge playing our Player Piano and I would drift off to sleep listening to some piece of Classical music.

In one of our cars that we owned I found a pipe one day and I asked him what it was for. He told me that he was trying to learn how to smoke but couldn’t quite get the hang of it cause it made him cough. Good job he didn’t eh.

In the School holiday’s Brian and I would catch the train into town and go and visit Dad at work. He would buy us a pie for lunch which was a real treat and we would sit in Miss Tate’s room and have lunch. That is where I met George Bell a great friend of my Father’s and they would play the Cello together and that was quite exciting too. Dad also had and played a Recorder he had a big one at work and a smaller one at home. Mum said he wasn’t very good at it but at work there was no criticism.

I only saw my Father cry once when I was a child and that was after a phone call telling him that his Father had died. We all stood together in a circle and had a big hug while Dad cried.

Dad often went away on Business trips to Wellington and he would visit his Father who lived there with his Third wife.

Every time Dad came home he would bring us a present and I came to wait impatiently for him to open his suitcase up to see what his gift was going to be .He bought me lots of dolls because he knew I loved them and I think even when I was 12 all I wanted for my Birthday was a doll.

Friday 6 August 2010

Hiroshima 65 years on

Today as we remember the tragic bombing of Hiroshima, I would like to write about a man who taught me of the evils of nuclear bombs, Warrington Taylor, a Dunedin lawyer of exceptional courage and conviction.

What an influence Warrington Taylor had on me.

Karitane beach 40 km north of Dunedin, is a peaceful place. In January 1965, I sat on a sandhill with Warrington Taylor (photo left), watching fishing boats returning with the morning's catch. Warrington told me about Hiroshima, and how we must do everything within ouir powers to ensure no one ever uses an Atomic bomb again. I was 17 and more interested in rugby, athletics and the beautiful young girls that took their holidays at Karitane. Little did I know that this man would shape my life and I would spend 39 years doing humanitaerian work through his encouragment and inspiration.

Karitane Beach, Otago, New Zealand.

Let us salute this remarkable man from Dunedin who shaped NZ anti-nuclear stance, Warrington Taylor, who did so much to ensure that NZers were made aware of the horrors of nuclear weapons, and who contributed to the NZ Government banning nuclear powered ships, has been forgotten as a man who stood up to the fickle politicians of the day, was called a 'crank' by many of them, but his legacy is large. I leave it to Warrington's closest friend, famous cricket commentator Iain Galloway to tell us a little about the late Warrington Taylor.

" After the war, as my law studies had been delayed by five years of war, my father Bryce Thomson could think of no-one better than Warrington Taylor to take me for tutorials and our peacetime association only strengthened my wartime impressions of him as a man of complete integrity and sincerity, outstanding intellectual gifts and blessed with a delightful sense of humour which stood him is such good stead when he faced from time to time rejection of his innovative if unusual plans and principles. Those lawyers here today will well remember how, for a period, Warrington signed all his cheques, trust account and personal, with the proviso that they be paid provided we weren’t all destroyed by nuclear explosion, how every year at our Annual Meeting he would politely seek permission to introduce a motion relating to nuclear disarmament only to be told that it was not relevant to the business of the Annual Meeting, a ruling he always accepted with dignity and good grace."

I would now like to post further information on Hiroshima today.

On Aug. 6 every year, Hiroshima remembers the 1945 atomic attack on the city. Kyoko Niiyama, who grew up in Hiroshima, is currently doing an internship at the city's Peace Memorial Museum.

Hiroshima was largely destroyed 65 years ago in the world's first attack using a nuclear bomb. The bomb, dropped by a US Air Force plane, killed tens of thousands and destroyed an entire generation in the city. Six decades later, Hiroshima is fighting to keep the memory of the attack alive.

The nuclear bomb and small origami cranes -- for Kyoko Niiyama, the two images are inseparable. "Each of the paper birds tells the sad story of my city, but they also represent its hopes and strengths," the 20-year-old says.

When she was at school, she also tried to fold her own cranes, she says. Just as Sadako Sasaki once did. Every child in Hiroshima knows Sasaki's story -- and entire classrooms make pilgrimages each year to the section of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial dedicated to her, where they hang their own origami cranes on strings.

Sadoko Sasaki was two years old when the first atomic bomb exploded in her hometown. She died at the age of 12 of leukemia, a disease many children fell victim to due to radiation from the bomb. During her final days in the hospital, a friend told Sasaki that anyone who folded 1,000 origami cranes could make a wish to God.

For origami paper, she used packing materials, newspapers and magazines. Other patients and friends brought her sheets of paper. The 12-year-old valiantly folded her origami, day in, day out. She managed to fold 1,000 cranes within the course of a month. But her wish of recovery was never fulfilled. Sasaki died on Oct. 25, 1955. As her parents encouraged her to eat more on the day of her death, she asked for tea with rice. "It tastes very good," were the girl's final words.

An exhibit in Hiroshima's Peace Memorial Museum shows origami cranes that Sadako Sasaki, a victim of the atomic bomb who suffered from leukemia, folded in the vain hope of getting better. For Kyoko Niiyama, it is one of the museum's most moving exhibits.

Kyoko Niiyama knows the story well, but sometimes she still struggles to control herself when she tells it. Possibly because it reminds her of her grandmother, who herself is a hibakusha, the Japanese word used to describe those who survived the nuclear bombings in Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

One of the stories her grandmother told her about August 6, 1945, is the one about her great-grandfather, whose body was never found. His body was either burned to the point of non-recognition or was completely incinerated by the explosion. "My grandmother still says today that she was never able to accept the death of her father because his fate was never clarified," the 20-year-old says. "It is a pain that never goes away."

Will Hollywood Ever Make an Objective Movie about Hiroshima?

"Hiroshima is a special city with a message," says Niiyama, who wants to become a journalist. She is currently completing an internship at Hiroshima's Peace Memorial Museum. It's an enormous, modern building, filled inside with exhibits on the unimaginable. One exhibit is a glass display case holding cranes that were folded by Sadoko Sasaki. The museum is also filled with photos, giant models and even tiles that were melted in the heat of the firestorm created by the blast.

The exhibits at the museum are very moving, and that is important to Niiyama. "We cannot forget the past," she says. "Of course we must also remember the crimes that were committed by our own military during World War II." Even 65 years after the end of the war, Japan still has a hard time coming to terms with its own history.

It's a problem, however, that isn't exlusive to Japan. Niiyama learned that during a year abroad, when she studied at a college in the United States. "To me, Hiroshima's message is not an indictment, but rather a warning for peace and against the nuclear bomb," she says. "I would have really liked to have told my fellow students in the US a lot about my hometown and its history," she says. But she says people had little interest in those stories.

Niiyama said her experience was that America's telling of history comes through overblown movies like "Pearl Harbor." She says she found there was a lack of any real discussion about the dropping of nuclear bombs in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. "We will probably have to wait an eternity for an objective Hollywood film about the victims of Hiroshima," Niiyama says, sounding a little bitter.

Part 2: Hiroshima Is Slowly Forgetting Its Own History

But even Hiroshima itself, the city where the first nuclear bomb was dropped, is slowly starting to forget its past. "All I have to do is look at my 16-year-old brother," she says. "The dropping of the nuclear bomb is only a thing of the distant past for him and other people his age. He doesn't even take the time to listen to our grandmother's stories," she says.

Niiyama then takes us through the expansive memorial park, which has several monuments including the Peace Bell, to the so-called A-Bomb Dome. The memorial is comprised of the ruins of one of the few buildings whose walls remained standing after the dropping of the bomb, even if the people behind those walls were incinerated. Now the building's steel dome points up toward the clouded sky. The scene still has the power to shock.

"Sometimes couples have photographs taken of themselves standing in front of it, smiling," says Kyoko Niijama, something that she finds "bizarre." An expensive restaurant on the river bank is located just a stone's throw from the peace monument.

The A-Bomb Dome is the ruins of one of the few buildings whose walls remained standing after the dropping of the bomb. This photo was taken by the US military after the bomb was dropped.

On August 6, Hiroshima takes a stand against forgetting. The city holds a large memorial ceremony with tens of thousands of visitors in the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park every year on the anniversary of the bombing. "And many schools continue to examine the issue," says Niiyama.

For example, the public Motomachi High School participated in an art project with hibakusha, where contemporary witnesses told students about the bombing. The pictures that the students later painted are disturbingly intense. One student, 17-year-old Miho Tokunaga, created a picture showing people burned in the explosion crossing a bridge. The naked, bleeding figures look like ghosts. It does not look as if a teenager painted the picture.

"It was clear to me that, no matter how hard I tried, I would never do justice to the sad stories of Ms. Watanabe, one of the hibakusha," the student said, looking serious. She traveled to the location that she depicts in the painting to see it first hand. "For the first time I really became aware of what happened back then, because one of the survivors told me about it." Before that, she admits, she hadn't given the subject much thought. "But what will happen when one day there are no more living witnesses? I think many people will forget."

It's a concern that is shared by Hotsuma Abe, a retiree who works as a part-time teacher at Motomachi High School. "I was shocked when I heard that some schools in Hiroshima have cut their peace lessons from the curriculum," the teacher says.

Survivors Still Die of Cancer Today

For Dr. Hiroo Dohy, however, forgetting will be impossible. He is head of the division for atomic bomb survivors at Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital. The hospital was already there when the bomb fell on Hiroshima and was severely damaged in the blast. Although many nurses and doctors lost their lives, and the surviving staff did not know what had happened to their relatives, the hospital remained in continuous operation. That's something the staff are still proud of at the hospital today. It was not until 1993 that the old buildings were replaced by a new building.

In the Atomic-Bomb Survivors Hospital Division, victims were still suffering and dying decades after the bombing. Even today, the hospital still has patients who are victims of the radiation they were exposed to then, who suffer from, among other complaints, cancers of the thyroid, lung, breast or genitals. "The closer they were to the epicenter at the time, the higher was the risk that they would later develop an illness," Hiroo Dohy explains. The fear of cancer is something that has accompanied many hibakusha their whole lives.

Part of the old masonry still stands in front of the hospital's entrance. It was kept as a monument, along with the building's twisted steel frame that reminds viewers of the massive blast wave. "This too is part of my city," says Niiyama. "Most of the tourist sights tell a sad story."

When she was at school, she also tried to fold her own cranes, she says. Just as Sadako Sasaki once did. Every child in Hiroshima knows Sasaki's story -- and entire classrooms make pilgrimages each year to the section of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial dedicated to her, where they hang their own origami cranes on strings.

Sadoko Sasaki was two years old when the first atomic bomb exploded in her hometown. She died at the age of 12 of leukemia, a disease many children fell victim to due to radiation from the bomb. During her final days in the hospital, a friend told Sasaki that anyone who folded 1,000 origami cranes could make a wish to God.

For origami paper, she used packing materials, newspapers and magazines. Other patients and friends brought her sheets of paper. The 12-year-old valiantly folded her origami, day in, day out. She managed to fold 1,000 cranes within the course of a month. But her wish of recovery was never fulfilled. Sasaki died on Oct. 25, 1955. As her parents encouraged her to eat more on the day of her death, she asked for tea with rice. "It tastes very good," were the girl's final words.

Kyoko Niiyama knows the story well, but sometimes she still struggles to control herself when she tells it. Possibly because it reminds her of her grandmother, who herself is a hibakusha, the Japanese word used to describe those who survived the nuclear bombings in Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

One of the stories her grandmother told her about August 6, 1945, is the one about her great-grandfather, whose body was never found. His body was either burned to the point of non-recognition or was completely incinerated by the explosion. "My grandmother still says today that she was never able to accept the death of her father because his fate was never clarified," the 20-year-old says. "It is a pain that never goes away."

What an influence Warrington Taylor had on me.

Karitane beach 40 km north of Dunedin, is a peaceful place. In January 1965, I sat on a sandhill with Warrington Taylor (photo left), watching fishing boats returning with the morning's catch. Warrington told me about Hiroshima, and how we must do everything within ouir powers to ensure no one ever uses an Atomic bomb again. I was 17 and more interested in rugby, athletics and the beautiful young girls that took their holidays at Karitane. Little did I know that this man would shape my life and I would spend 39 years doing humanitaerian work through his encouragment and inspiration.

Karitane Beach, Otago, New Zealand.

Let us salute this remarkable man from Dunedin who shaped NZ anti-nuclear stance, Warrington Taylor, who did so much to ensure that NZers were made aware of the horrors of nuclear weapons, and who contributed to the NZ Government banning nuclear powered ships, has been forgotten as a man who stood up to the fickle politicians of the day, was called a 'crank' by many of them, but his legacy is large. I leave it to Warrington's closest friend, famous cricket commentator Iain Galloway to tell us a little about the late Warrington Taylor.

" After the war, as my law studies had been delayed by five years of war, my father Bryce Thomson could think of no-one better than Warrington Taylor to take me for tutorials and our peacetime association only strengthened my wartime impressions of him as a man of complete integrity and sincerity, outstanding intellectual gifts and blessed with a delightful sense of humour which stood him is such good stead when he faced from time to time rejection of his innovative if unusual plans and principles. Those lawyers here today will well remember how, for a period, Warrington signed all his cheques, trust account and personal, with the proviso that they be paid provided we weren’t all destroyed by nuclear explosion, how every year at our Annual Meeting he would politely seek permission to introduce a motion relating to nuclear disarmament only to be told that it was not relevant to the business of the Annual Meeting, a ruling he always accepted with dignity and good grace."

I would now like to post further information on Hiroshima today.

On Aug. 6 every year, Hiroshima remembers the 1945 atomic attack on the city. Kyoko Niiyama, who grew up in Hiroshima, is currently doing an internship at the city's Peace Memorial Museum.

Hiroshima was largely destroyed 65 years ago in the world's first attack using a nuclear bomb. The bomb, dropped by a US Air Force plane, killed tens of thousands and destroyed an entire generation in the city. Six decades later, Hiroshima is fighting to keep the memory of the attack alive.

The nuclear bomb and small origami cranes -- for Kyoko Niiyama, the two images are inseparable. "Each of the paper birds tells the sad story of my city, but they also represent its hopes and strengths," the 20-year-old says.

When she was at school, she also tried to fold her own cranes, she says. Just as Sadako Sasaki once did. Every child in Hiroshima knows Sasaki's story -- and entire classrooms make pilgrimages each year to the section of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial dedicated to her, where they hang their own origami cranes on strings.

Sadoko Sasaki was two years old when the first atomic bomb exploded in her hometown. She died at the age of 12 of leukemia, a disease many children fell victim to due to radiation from the bomb. During her final days in the hospital, a friend told Sasaki that anyone who folded 1,000 origami cranes could make a wish to God.

For origami paper, she used packing materials, newspapers and magazines. Other patients and friends brought her sheets of paper. The 12-year-old valiantly folded her origami, day in, day out. She managed to fold 1,000 cranes within the course of a month. But her wish of recovery was never fulfilled. Sasaki died on Oct. 25, 1955. As her parents encouraged her to eat more on the day of her death, she asked for tea with rice. "It tastes very good," were the girl's final words.

An exhibit in Hiroshima's Peace Memorial Museum shows origami cranes that Sadako Sasaki, a victim of the atomic bomb who suffered from leukemia, folded in the vain hope of getting better. For Kyoko Niiyama, it is one of the museum's most moving exhibits.

Kyoko Niiyama knows the story well, but sometimes she still struggles to control herself when she tells it. Possibly because it reminds her of her grandmother, who herself is a hibakusha, the Japanese word used to describe those who survived the nuclear bombings in Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

One of the stories her grandmother told her about August 6, 1945, is the one about her great-grandfather, whose body was never found. His body was either burned to the point of non-recognition or was completely incinerated by the explosion. "My grandmother still says today that she was never able to accept the death of her father because his fate was never clarified," the 20-year-old says. "It is a pain that never goes away."

Will Hollywood Ever Make an Objective Movie about Hiroshima?

"Hiroshima is a special city with a message," says Niiyama, who wants to become a journalist. She is currently completing an internship at Hiroshima's Peace Memorial Museum. It's an enormous, modern building, filled inside with exhibits on the unimaginable. One exhibit is a glass display case holding cranes that were folded by Sadoko Sasaki. The museum is also filled with photos, giant models and even tiles that were melted in the heat of the firestorm created by the blast.

The exhibits at the museum are very moving, and that is important to Niiyama. "We cannot forget the past," she says. "Of course we must also remember the crimes that were committed by our own military during World War II." Even 65 years after the end of the war, Japan still has a hard time coming to terms with its own history.

It's a problem, however, that isn't exlusive to Japan. Niiyama learned that during a year abroad, when she studied at a college in the United States. "To me, Hiroshima's message is not an indictment, but rather a warning for peace and against the nuclear bomb," she says. "I would have really liked to have told my fellow students in the US a lot about my hometown and its history," she says. But she says people had little interest in those stories.

Niiyama said her experience was that America's telling of history comes through overblown movies like "Pearl Harbor." She says she found there was a lack of any real discussion about the dropping of nuclear bombs in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. "We will probably have to wait an eternity for an objective Hollywood film about the victims of Hiroshima," Niiyama says, sounding a little bitter.

Part 2: Hiroshima Is Slowly Forgetting Its Own History

But even Hiroshima itself, the city where the first nuclear bomb was dropped, is slowly starting to forget its past. "All I have to do is look at my 16-year-old brother," she says. "The dropping of the nuclear bomb is only a thing of the distant past for him and other people his age. He doesn't even take the time to listen to our grandmother's stories," she says.

Niiyama then takes us through the expansive memorial park, which has several monuments including the Peace Bell, to the so-called A-Bomb Dome. The memorial is comprised of the ruins of one of the few buildings whose walls remained standing after the dropping of the bomb, even if the people behind those walls were incinerated. Now the building's steel dome points up toward the clouded sky. The scene still has the power to shock.

"Sometimes couples have photographs taken of themselves standing in front of it, smiling," says Kyoko Niijama, something that she finds "bizarre." An expensive restaurant on the river bank is located just a stone's throw from the peace monument.

Modern-day Hiroshima starts behind the A-Bomb Dome peace memorial. With its new high-rises and shining facades, all of which are very clean and somewhat dull, it resembles a typical Japanese city, and is perhaps even a bit more sophisticated and modern than cities in other parts of the country. The city has a large covered shopping area and an entertainment district where groups of drunken salarymen totter uncertainly to taxis in the wee hours. Neon signs light up the downtown area at night, and pachinko machines rattle with a deafening noise in the casinos. Billboards promote the local baseball team, Hiroshima Toyo Carp, which plays in Japan's top league.

The A-Bomb Dome is the ruins of one of the few buildings whose walls remained standing after the dropping of the bomb. This photo was taken by the US military after the bomb was dropped.

On August 6, Hiroshima takes a stand against forgetting. The city holds a large memorial ceremony with tens of thousands of visitors in the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park every year on the anniversary of the bombing. "And many schools continue to examine the issue," says Niiyama.

For example, the public Motomachi High School participated in an art project with hibakusha, where contemporary witnesses told students about the bombing. The pictures that the students later painted are disturbingly intense. One student, 17-year-old Miho Tokunaga, created a picture showing people burned in the explosion crossing a bridge. The naked, bleeding figures look like ghosts. It does not look as if a teenager painted the picture.

"It was clear to me that, no matter how hard I tried, I would never do justice to the sad stories of Ms. Watanabe, one of the hibakusha," the student said, looking serious. She traveled to the location that she depicts in the painting to see it first hand. "For the first time I really became aware of what happened back then, because one of the survivors told me about it." Before that, she admits, she hadn't given the subject much thought. "But what will happen when one day there are no more living witnesses? I think many people will forget."

It's a concern that is shared by Hotsuma Abe, a retiree who works as a part-time teacher at Motomachi High School. "I was shocked when I heard that some schools in Hiroshima have cut their peace lessons from the curriculum," the teacher says.

Survivors Still Die of Cancer Today

For Dr. Hiroo Dohy, however, forgetting will be impossible. He is head of the division for atomic bomb survivors at Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital. The hospital was already there when the bomb fell on Hiroshima and was severely damaged in the blast. Although many nurses and doctors lost their lives, and the surviving staff did not know what had happened to their relatives, the hospital remained in continuous operation. That's something the staff are still proud of at the hospital today. It was not until 1993 that the old buildings were replaced by a new building.

In the Atomic-Bomb Survivors Hospital Division, victims were still suffering and dying decades after the bombing. Even today, the hospital still has patients who are victims of the radiation they were exposed to then, who suffer from, among other complaints, cancers of the thyroid, lung, breast or genitals. "The closer they were to the epicenter at the time, the higher was the risk that they would later develop an illness," Hiroo Dohy explains. The fear of cancer is something that has accompanied many hibakusha their whole lives.

Part of the old masonry still stands in front of the hospital's entrance. It was kept as a monument, along with the building's twisted steel frame that reminds viewers of the massive blast wave. "This too is part of my city," says Niiyama. "Most of the tourist sights tell a sad story."

When she was at school, she also tried to fold her own cranes, she says. Just as Sadako Sasaki once did. Every child in Hiroshima knows Sasaki's story -- and entire classrooms make pilgrimages each year to the section of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial dedicated to her, where they hang their own origami cranes on strings.

Sadoko Sasaki was two years old when the first atomic bomb exploded in her hometown. She died at the age of 12 of leukemia, a disease many children fell victim to due to radiation from the bomb. During her final days in the hospital, a friend told Sasaki that anyone who folded 1,000 origami cranes could make a wish to God.

For origami paper, she used packing materials, newspapers and magazines. Other patients and friends brought her sheets of paper. The 12-year-old valiantly folded her origami, day in, day out. She managed to fold 1,000 cranes within the course of a month. But her wish of recovery was never fulfilled. Sasaki died on Oct. 25, 1955. As her parents encouraged her to eat more on the day of her death, she asked for tea with rice. "It tastes very good," were the girl's final words.

Kyoko Niiyama knows the story well, but sometimes she still struggles to control herself when she tells it. Possibly because it reminds her of her grandmother, who herself is a hibakusha, the Japanese word used to describe those who survived the nuclear bombings in Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

One of the stories her grandmother told her about August 6, 1945, is the one about her great-grandfather, whose body was never found. His body was either burned to the point of non-recognition or was completely incinerated by the explosion. "My grandmother still says today that she was never able to accept the death of her father because his fate was never clarified," the 20-year-old says. "It is a pain that never goes away."

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)