As a teenager I spent many hours over a number of years listening to a wise man, Warrington Taylor. A lawyer by profession who had read everything available in English on Hiroshima, Nagasaki and on nuclear fuel, nuclear power and nuclear weapons.

He said simply one day when sitting overlooking the river that flows into the small fishing port at Karitane, Otago, New Zealand, " if we don't continue to fight nuclear disarmament and the use of nuclear power, it will be the death of us." First there was Chernobyl, and now what is happening in Japan.

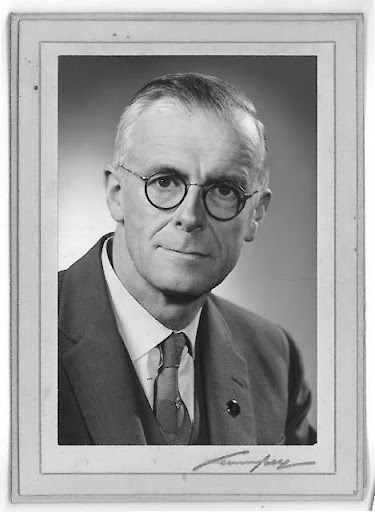

On 22 February 2010 he lost his son Brian Warrington Taylor in the tragic Christchurch earthquake and now his nightmare of a nuclear holocaust is a possiblity. (Photo: right) Brian used to play the guitar well, and we used to sing the Joan Baez song 'The Times they are a changing' often and Warrington loved the words.

So to Warrington and Brian, I believe you are together now and you will be looking down on your nuclear prediction, A world destroying itself. I would like to write a little about a man who did so much for nuclear disarmament legislation in new Zealand, and for me personally.

Having known Warrington Taylor's very clear and outspoken (at the time) views on nuclear holocausts and accidents ocurring, I can only write in support of a man who in 1960, was publicly ridiculed, when he stood for an Independent candidate on the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament ticket in Dunedin Central electorate in the general elections.. He was labelled a crackpot, certainly eccentric and got few votes.

He was a pioneer in New Zealand's actions and policies on anti-nuclear legislation.Warrington Taylor was a generation ahead of his time. He had a huge influence on future generations of NZ leaders and politicians and his acts of courage and determination led to barring nuclear-armed ships into New Zealand..

In 1984, Prime Minister David Lange barred nuclear-powered or nuclear-armed ships from using New Zealand ports or entering New Zealand waters. Under the New Zealand Nuclear Free Zone, Disarmament, and Arms Control Act 1987,territorial sea, land and airspace of New Zealand became nuclear-free zones. This has since become a sacrosanct touchstone of New Zealand foreign policy.

The Act prohibits "entry into the internal waters of New Zealand 12 miles (22.2 km) radius by any ship whose propulsion is wholly or partly dependent on nuclear power" and bans the dumping of radioactive waste within the nuclear-free zone, as well as prohibiting any New Zealand citizen or resident "to manufacture, acquire, possess, or have any control over any nuclear explosive device."The nuclear-free zone Act does not make building land-based nuclear power plants illegal.

After the Disarmament and Arms Control Act was passed by the Lange Labour government, the United States government suspended its ANZUS obligations to New Zealand. The legislation was a milestone in New Zealand's development as a nation and seen as an important act of sovereignty, self-determination and cultural identity. New Zealand's three decade anti-nuclear campaign is the only successful movement of its type in the world which resulted in the nation's nuclear-free zone status being enshrined in legislation.

But first, a bit more history:

Initial seeds were sown for New Zealand's 1987 nuclear free zone legislation in the late 1950s with the formation of the local Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) organisation between 1957-59. Warrington Taylor led the CND movement in Dunedin, my home town, and further afield. In 1959, responding to rising public concern following the British H-Bomb tests in Australia and the Pacific, New Zealand voted in the UN to condemn nuclear testing while the UK, US and France voted against, and Australia abstained. In 1961, CND urged the New Zealand government to declare that it would not acquire or use nuclear weapons and to withdraw from nuclear alliances such as ANZUS. In 1963, the Auckland CND campaign submitted its 'No Bombs South of the Line' petition to the New Zealand parliament with 80,238 signatures calling on the government to sponsor an international conference to discuss establishing a nuclear-free-zone in the southern hemisphere. It was the biggest petition in the nation since the one in 1893 which demanded that women must have the right to vote.

Mururoa

Mururoa atoll, and its sister atoll Fangataufa, in French Polynesia in the southern Pacific Ocean were officially established by France as a nuclear test site on September 21, 1962 and extensive nuclear testing occurred between 1966 and 1996. The first nuclear test, codenamed Aldebaran, was conducted on July 2, 1966 and forty-one atmospheric nuclear tests were conducted at Mururoa between 1966 and 1974.

In March 1976 over 20 anti nuclear and environmental groups, including Greenpeace and Friends of the Earth, met in Wellington and formed a loose coalition called the Campaign for Non-Nuclear Futures (CNNF). The coalitions mandate was to oppose the introduction of nuclear power and to promote renewable energy alternatives such as wind, wave, solar and geothermal power. They launched Campaign Half Million. CNNF embarked on a national education exercise producing the largest petition against nuclear power in New Zealand's history with 333,087 signatures by October 1976. This represented over 10% of New Zealand's total population of 3 million. At this time, New Zealand's only ever nuclear reactor was a small sub-critical reactor that had been installed at the School of Engineering of the University of Canterbury in 1962. It had been given by the United States' Atoms for Peace programme and was used for training electrical engineers in nuclear techniques. It was dismantled in 1981.

Regional anti-nuclear sentiment was consolidated in 1985 when eight of the thirteen South Pacific Forum nations signed the South Pacific Nuclear Free Zone Treaty or Treaty of Rarotonga.

Mururoa protests

Community inspired anti-nuclear sentiments largely contributed to the New Zealand Labour Party election victory under Norman Kirk in 1972. Also in 1972, the International Court of Justice (case launched by Australia and New Zealand), ordered that the French cease atmospheric nuclear testing at Mururoa atoll.[18] However, the French ignored this ruling. Mururoa was the site of numerous protests by various vessels, including the Rainbow Warrior. In a symbolic act of protest the Kirk government sent two of its navy frigates, HMNZS Canterbury and Otago, into the test zone area in 1973. A Cabinet Minister (Fraser Colman) was randomly selected to accompany this official New Zealand Government protest fleet. This voyage included a number of local kiwi peace organisations who had organised an international flotilla of protest yachts that accompanied the frigates into the Mururoa zone. Many of the early NZ peace activists and organisations were enthusiastic young hippies and students, many of whom were involved with the counter-culture and the original opposition to the Vietnam War movements.

But let's remember and thank Warrington Taylor for his contribution to making New Zealand a nuclear free country.

Meanwhile, Japan has raised the alert level at its quake-damaged nuclear plant from four to five on a seven-point international scale of atomic incidents.

The crisis at the Fukushima Daiichi site, previously rated as a local problem, is now regarded as having "wider consequences".

The UN says the battle to stabilise the plant is a race against time.

The crisis was prompted by last week's huge quake and tsunami, which has left at least 17,000 people dead or missing.

Japanese nuclear officials said core damage to reactors 2 and 3 had prompted the raising of the severity grade.

The 1979 incident at Three Mile Island in the US was also rated at five on the scale, whereas the 1986 Chernobyl disaster was rated at seven.

Panic-buying

Further heavy snowfall overnight all but ended hopes of rescuing anyone else from the rubble after the 9.0-magnitude quake and tsunami.

Millions of people have been affected by the disaster - many survivors have been left without water, electricity, fuel or enough food; hundreds of thousands are homeless.

Analysis

Japan's upgrading of the Fukushima incident from severity four to five stems from concerns about the reactors in buildings 1, 2 and 3, rather than the cooling ponds storing spent fuel.

Level five is defined as an "accident with wider consequences". This was the level given to the 1957 reactor fire at Windscale in the UK and the partial meltdown of the Three Mile Island plant in the US in 1979.

Both met the level five definition of "limited release" of radioactive materials to the wider environment.

Windscale is believed to have caused about 200 cases of cancer, whereas reports into the Three Mile Island incident suggest there were no health impacts outside the site.

French and US officials had previously said the Fukushima situation was more serious than Japanese evaluations suggested.

Higher radiation levels than normal have been recorded in a few places 30km from the site, but in Tokyo, they were reported to be normal.

The national police say 6,911 people are known to have died in the disaster, and 10,316 are still missing.

On Friday, people across Japan observed a minute's silence at 1446 (0546 GMT), exactly one week after the disaster.

As the country paused to remember, relief workers toiling in the ruins bowed their heads, and some elderly survivors in evacuation centres wept.

Japanese officials continue to try to reassure people that the radiation risk is virtually nil outside the 30-km (18-mile) exclusion zone around the plant.

But foreign governments are taking wider precautions - Spain has joined Britain, the US and other countries in organising the evacuation of any of their citizens who are concerned.

And panic has spread overseas, with shops in parts of the US being stripped of iodine pills, which can protect against radiation, and Asian airports scanning passengers from Japan for possible contamination.

Shoppers in China have been panic-buying salt in the mistaken belief that it can guard against radiation exposure.

Meanwhile, Prime Minister Naoto Kan told a national television address: "We will rebuild Japan from scratch. We must all share this resolve."

He said the natural disaster and nuclear crisis were a "great test for the Japanese people", but exhorted them all to persevere..

International Atomic Energy Agency chief Yukiya Amano arrived earlier in Tokyo and warned the Fukushima crisis was a "race against the clock".

The IAEA announced it would hold a special board meeting on Monday to discuss Mr Amano's findings.

The Fukushima plant's operator Tokyo Electric Power (Tepco) said it was not ruling out the option of entombing the plant in concrete to prevent a radiation leak; a similar method was used at Chernobyl.

Fractured Fukushima

Reactor 1: Fuel rods damaged after explosion last Saturday

Reactor 2: Damage to the core, prompted by a blast on Tues, helped prompt raising of the nuclear alert level

Reactor 3: Contains plutonium, core damaged by explosion on Monday; roof blown off building; water level in fuel pools said to be dangerously low

Reactor 4: Hit by explosion on Tuesday, fire on Wednesday; roof blown off building; water level in fuel pools said to be dangerously low

Reactors 5 & 6: Spent fuel pool temperatures way above normal levels

Military fire trucks have been spraying the plant's overheating reactor units for a second day.

Water in at least two fuel pools - in reactor buildings 3 and 4 - is believed to be dangerously low, exposing the stored fuel rods.

This increases the chance of radioactive substances being released from the rods.

An electricity line has been bulldozed through to the site and engineers are racing to connect it, but they are being hampered by radiation.

The plant's operators need the power cable to restart water pumps that pour cold water on the reactor units.

Military helicopters which dropped water from above on Thursday have been kept on standby.

Steam rises from the No.3 reactor at the Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear power complex, March 16.

Damage to the No. 4 reactor at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power complex.

Damage to the No. 4 reactor at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power complex.

Medical staff use a Geiger counter to screen a woman for possible radiation exposure at a public welfare centre in Hitachi City, Ibaraki.

Tokyo Electric Co. employees in charge of public relations use a photo of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear complex to explain the situation during a press conference.

A radiation dosimeter measures radiation levels in Shibuya, Tokyo.

The No.3 nuclear reactor of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant is seen burning after a blast following an earthquake and tsunami in this satellite image.

A doctor checks uses a giger counter to check the level of radiation on a woman while a soldier in gas mask looks on at a radiation treatment centre in Nihonmatsu city in Fukushima prefecture.

Smoke rises from Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power complex in this still image from video footage.

This image from Japan's NHK public television via Kyodo News shows the Fukushima Dai-ichi power plant's Unit 3 after Monday's explosion.

An official scans for signs of radiation in Nihonmatsu City after radiation leaked from the earthquake-damaged Fukushima Daini nuclear station.

A girl at a makeshift facility to screen, cleanse and isolate people with high radiation levels, looks at her dog through a window in Nihonmatsu.

Futaba Kosei Hospital patients disembark after being evacuated from a hospital near the troubled Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear complex. They might have been exposed to radiation while waiting for evacuation.

Officials in protective gear stand next to people from the evacuation area near the Fukushima Daini nuclear plant.

An official in protective gear talks to a woman who is from the evacuation area near the Fukushima Daini nuclear plant.

The damaged roof of reactor number No. 1 at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant after an explosion that blew off the upper part of the structure.

.

He said simply one day when sitting overlooking the river that flows into the small fishing port at Karitane, Otago, New Zealand, " if we don't continue to fight nuclear disarmament and the use of nuclear power, it will be the death of us." First there was Chernobyl, and now what is happening in Japan.

On 22 February 2010 he lost his son Brian Warrington Taylor in the tragic Christchurch earthquake and now his nightmare of a nuclear holocaust is a possiblity. (Photo: right) Brian used to play the guitar well, and we used to sing the Joan Baez song 'The Times they are a changing' often and Warrington loved the words.

So to Warrington and Brian, I believe you are together now and you will be looking down on your nuclear prediction, A world destroying itself. I would like to write a little about a man who did so much for nuclear disarmament legislation in new Zealand, and for me personally.

Having known Warrington Taylor's very clear and outspoken (at the time) views on nuclear holocausts and accidents ocurring, I can only write in support of a man who in 1960, was publicly ridiculed, when he stood for an Independent candidate on the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament ticket in Dunedin Central electorate in the general elections.. He was labelled a crackpot, certainly eccentric and got few votes.

He was a pioneer in New Zealand's actions and policies on anti-nuclear legislation.Warrington Taylor was a generation ahead of his time. He had a huge influence on future generations of NZ leaders and politicians and his acts of courage and determination led to barring nuclear-armed ships into New Zealand..

In 1984, Prime Minister David Lange barred nuclear-powered or nuclear-armed ships from using New Zealand ports or entering New Zealand waters. Under the New Zealand Nuclear Free Zone, Disarmament, and Arms Control Act 1987,territorial sea, land and airspace of New Zealand became nuclear-free zones. This has since become a sacrosanct touchstone of New Zealand foreign policy.

The Act prohibits "entry into the internal waters of New Zealand 12 miles (22.2 km) radius by any ship whose propulsion is wholly or partly dependent on nuclear power" and bans the dumping of radioactive waste within the nuclear-free zone, as well as prohibiting any New Zealand citizen or resident "to manufacture, acquire, possess, or have any control over any nuclear explosive device."The nuclear-free zone Act does not make building land-based nuclear power plants illegal.

After the Disarmament and Arms Control Act was passed by the Lange Labour government, the United States government suspended its ANZUS obligations to New Zealand. The legislation was a milestone in New Zealand's development as a nation and seen as an important act of sovereignty, self-determination and cultural identity. New Zealand's three decade anti-nuclear campaign is the only successful movement of its type in the world which resulted in the nation's nuclear-free zone status being enshrined in legislation.

But first, a bit more history:

Initial seeds were sown for New Zealand's 1987 nuclear free zone legislation in the late 1950s with the formation of the local Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) organisation between 1957-59. Warrington Taylor led the CND movement in Dunedin, my home town, and further afield. In 1959, responding to rising public concern following the British H-Bomb tests in Australia and the Pacific, New Zealand voted in the UN to condemn nuclear testing while the UK, US and France voted against, and Australia abstained. In 1961, CND urged the New Zealand government to declare that it would not acquire or use nuclear weapons and to withdraw from nuclear alliances such as ANZUS. In 1963, the Auckland CND campaign submitted its 'No Bombs South of the Line' petition to the New Zealand parliament with 80,238 signatures calling on the government to sponsor an international conference to discuss establishing a nuclear-free-zone in the southern hemisphere. It was the biggest petition in the nation since the one in 1893 which demanded that women must have the right to vote.

Mururoa

Mururoa atoll, and its sister atoll Fangataufa, in French Polynesia in the southern Pacific Ocean were officially established by France as a nuclear test site on September 21, 1962 and extensive nuclear testing occurred between 1966 and 1996. The first nuclear test, codenamed Aldebaran, was conducted on July 2, 1966 and forty-one atmospheric nuclear tests were conducted at Mururoa between 1966 and 1974.

In March 1976 over 20 anti nuclear and environmental groups, including Greenpeace and Friends of the Earth, met in Wellington and formed a loose coalition called the Campaign for Non-Nuclear Futures (CNNF). The coalitions mandate was to oppose the introduction of nuclear power and to promote renewable energy alternatives such as wind, wave, solar and geothermal power. They launched Campaign Half Million. CNNF embarked on a national education exercise producing the largest petition against nuclear power in New Zealand's history with 333,087 signatures by October 1976. This represented over 10% of New Zealand's total population of 3 million. At this time, New Zealand's only ever nuclear reactor was a small sub-critical reactor that had been installed at the School of Engineering of the University of Canterbury in 1962. It had been given by the United States' Atoms for Peace programme and was used for training electrical engineers in nuclear techniques. It was dismantled in 1981.

Regional anti-nuclear sentiment was consolidated in 1985 when eight of the thirteen South Pacific Forum nations signed the South Pacific Nuclear Free Zone Treaty or Treaty of Rarotonga.

Mururoa protests

Community inspired anti-nuclear sentiments largely contributed to the New Zealand Labour Party election victory under Norman Kirk in 1972. Also in 1972, the International Court of Justice (case launched by Australia and New Zealand), ordered that the French cease atmospheric nuclear testing at Mururoa atoll.[18] However, the French ignored this ruling. Mururoa was the site of numerous protests by various vessels, including the Rainbow Warrior. In a symbolic act of protest the Kirk government sent two of its navy frigates, HMNZS Canterbury and Otago, into the test zone area in 1973. A Cabinet Minister (Fraser Colman) was randomly selected to accompany this official New Zealand Government protest fleet. This voyage included a number of local kiwi peace organisations who had organised an international flotilla of protest yachts that accompanied the frigates into the Mururoa zone. Many of the early NZ peace activists and organisations were enthusiastic young hippies and students, many of whom were involved with the counter-culture and the original opposition to the Vietnam War movements.

But let's remember and thank Warrington Taylor for his contribution to making New Zealand a nuclear free country.

Meanwhile, Japan has raised the alert level at its quake-damaged nuclear plant from four to five on a seven-point international scale of atomic incidents.

The crisis at the Fukushima Daiichi site, previously rated as a local problem, is now regarded as having "wider consequences".

The UN says the battle to stabilise the plant is a race against time.

The crisis was prompted by last week's huge quake and tsunami, which has left at least 17,000 people dead or missing.

Japanese nuclear officials said core damage to reactors 2 and 3 had prompted the raising of the severity grade.

The 1979 incident at Three Mile Island in the US was also rated at five on the scale, whereas the 1986 Chernobyl disaster was rated at seven.

Panic-buying

Further heavy snowfall overnight all but ended hopes of rescuing anyone else from the rubble after the 9.0-magnitude quake and tsunami.

Millions of people have been affected by the disaster - many survivors have been left without water, electricity, fuel or enough food; hundreds of thousands are homeless.

Analysis

Japan's upgrading of the Fukushima incident from severity four to five stems from concerns about the reactors in buildings 1, 2 and 3, rather than the cooling ponds storing spent fuel.

Level five is defined as an "accident with wider consequences". This was the level given to the 1957 reactor fire at Windscale in the UK and the partial meltdown of the Three Mile Island plant in the US in 1979.

Both met the level five definition of "limited release" of radioactive materials to the wider environment.

Windscale is believed to have caused about 200 cases of cancer, whereas reports into the Three Mile Island incident suggest there were no health impacts outside the site.

French and US officials had previously said the Fukushima situation was more serious than Japanese evaluations suggested.

Higher radiation levels than normal have been recorded in a few places 30km from the site, but in Tokyo, they were reported to be normal.

The national police say 6,911 people are known to have died in the disaster, and 10,316 are still missing.

On Friday, people across Japan observed a minute's silence at 1446 (0546 GMT), exactly one week after the disaster.

As the country paused to remember, relief workers toiling in the ruins bowed their heads, and some elderly survivors in evacuation centres wept.

Japanese officials continue to try to reassure people that the radiation risk is virtually nil outside the 30-km (18-mile) exclusion zone around the plant.

But foreign governments are taking wider precautions - Spain has joined Britain, the US and other countries in organising the evacuation of any of their citizens who are concerned.

And panic has spread overseas, with shops in parts of the US being stripped of iodine pills, which can protect against radiation, and Asian airports scanning passengers from Japan for possible contamination.

Shoppers in China have been panic-buying salt in the mistaken belief that it can guard against radiation exposure.

Meanwhile, Prime Minister Naoto Kan told a national television address: "We will rebuild Japan from scratch. We must all share this resolve."

He said the natural disaster and nuclear crisis were a "great test for the Japanese people", but exhorted them all to persevere..

International Atomic Energy Agency chief Yukiya Amano arrived earlier in Tokyo and warned the Fukushima crisis was a "race against the clock".

The IAEA announced it would hold a special board meeting on Monday to discuss Mr Amano's findings.

The Fukushima plant's operator Tokyo Electric Power (Tepco) said it was not ruling out the option of entombing the plant in concrete to prevent a radiation leak; a similar method was used at Chernobyl.

Fractured Fukushima

Reactor 1: Fuel rods damaged after explosion last Saturday

Reactor 2: Damage to the core, prompted by a blast on Tues, helped prompt raising of the nuclear alert level

Reactor 3: Contains plutonium, core damaged by explosion on Monday; roof blown off building; water level in fuel pools said to be dangerously low

Reactor 4: Hit by explosion on Tuesday, fire on Wednesday; roof blown off building; water level in fuel pools said to be dangerously low

Reactors 5 & 6: Spent fuel pool temperatures way above normal levels

Military fire trucks have been spraying the plant's overheating reactor units for a second day.

Water in at least two fuel pools - in reactor buildings 3 and 4 - is believed to be dangerously low, exposing the stored fuel rods.

This increases the chance of radioactive substances being released from the rods.

An electricity line has been bulldozed through to the site and engineers are racing to connect it, but they are being hampered by radiation.

The plant's operators need the power cable to restart water pumps that pour cold water on the reactor units.

Military helicopters which dropped water from above on Thursday have been kept on standby.

Steam rises from the No.3 reactor at the Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear power complex, March 16.

Damage to the No. 4 reactor at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power complex.

Damage to the No. 4 reactor at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power complex.

Medical staff use a Geiger counter to screen a woman for possible radiation exposure at a public welfare centre in Hitachi City, Ibaraki.

Tokyo Electric Co. employees in charge of public relations use a photo of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear complex to explain the situation during a press conference.

A radiation dosimeter measures radiation levels in Shibuya, Tokyo.

The No.3 nuclear reactor of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant is seen burning after a blast following an earthquake and tsunami in this satellite image.

A doctor checks uses a giger counter to check the level of radiation on a woman while a soldier in gas mask looks on at a radiation treatment centre in Nihonmatsu city in Fukushima prefecture.

Smoke rises from Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power complex in this still image from video footage.

This image from Japan's NHK public television via Kyodo News shows the Fukushima Dai-ichi power plant's Unit 3 after Monday's explosion.

An official scans for signs of radiation in Nihonmatsu City after radiation leaked from the earthquake-damaged Fukushima Daini nuclear station.

A girl at a makeshift facility to screen, cleanse and isolate people with high radiation levels, looks at her dog through a window in Nihonmatsu.

Futaba Kosei Hospital patients disembark after being evacuated from a hospital near the troubled Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear complex. They might have been exposed to radiation while waiting for evacuation.

Officials in protective gear stand next to people from the evacuation area near the Fukushima Daini nuclear plant.

An official in protective gear talks to a woman who is from the evacuation area near the Fukushima Daini nuclear plant.

The damaged roof of reactor number No. 1 at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant after an explosion that blew off the upper part of the structure.

.